Glossary of technical terms

- Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM)

The OECD defines ASM as “formal or informal mining operations with predominantly simplified forms of exploration, extraction, processing, and transportation. ASM is normally low capital-intensive and uses high labour-intensive technology. ‘ASM’ can include men and women working on an individual basis as well as those working in family groups, in partnership, or as members of cooperatives or other types of legal associations and enterprises involving hundreds of thousands of miners.”

- Blockchain

A blockchain is a distributed database that is used to maintain a continuously growing list of records called blocks. Once recorded, the data in any given block cannot be altered without corrupting the entire chain. It offers a way for transactions to be reliably recorded and traced through the assent of everyone in the supply chain. It is increasingly being used in supply chain mapping software by many providers as a method of inter-organisational record keeping.

- Conflict-affected and high-risk areas (CAHRAs)

According to the OECD due diligence guidance (OECD DDG), CAHRAs are characterised “by the presence of armed conflict, widespread violence or other risks of harm to people”. “High-risk areas are those where there is a high risk of conflict or of widespread or serious abuses as defined in paragraph 1 of annex II of the guidance.” The definition of a CAHRA in the EU regulation is coherent with the one provided by the OECD DDG.

- Conflict minerals reporting template (CMRT)

The Conflict Minerals Reporting Template (CMRT) is a free, standardised reporting template created by the RMI in collaboration with members of the RMI, AIAG, and JEITA. The CMRT facilitates the transfer of information through the supply chain regarding the mineral country of origin and the smelters and refiners being utilised. It supports compliance with legislation and adherence to the OECD DDG. The template also facilitates the identification of new smelters and refiners to potentially participate in independent third-party assurance programs, pursuant to OECD step 4. The CMRT is intended to benefit suppliers and their customers by promoting consistency and efficiency in the minerals due diligence data exchange declaration process. The CMRT is designed to follow the IPC-1755 conflict minerals data exchange standard. IT solution providers often allow companies to upload the CMRT in MS Excel format to input directly into the IT platforms.

- Corrective action plan

A corrective action plan is a step-by-step plan of action designed to address problems in a supply chain, most often used in audits. It should include concrete responsibilities and actions in prevention, mitigation and remediation, within a set time frame.

- Disclosure

According to the OECD, “enterprises should ensure that timely and accurate information is disclosed on all material matters regarding their activities, structure, financial situation, performance, ownership and governance. This information should be disclosed for the enterprise as a whole, and, where appropriate, along business lines or geographic areas. Disclosure policies of enterprises should be tailored to the nature, size and location of the enterprise, with due regard taken of costs, business confidentiality and other competitive concerns”.

- Dodd-Frank act section 1502

Legislation that requires Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reporting companies (as per sections 13[a] or 15[d] of the exchange act) in the US to identify and report whether ‘conflict minerals’ from DRC and its 9 surrounding countries are present in their supply chains. This law, which is currently undergoing revision, does not prohibit the use of ‘conflict minerals’.

- Downstream companies

All companies downstream of the refiners and smelters (see FAQ 5). Downstream companies include “metal traders and exchanges, bullion banks, other entities that do their own gold vaulting, component manufacturers, product manufacturers, original equipment manufacturers, jewellery manufacturers, retailers, and other companies using metals in the fabrication of products such as manufacturers and retailers of electronics equipment and/or medical devices”. (For more, see the due diligence guidance: towards conflict-free mineral supply chains. Specifically, the OECD easy to use guidance).

- Due diligence

The processes through which enterprises can identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their actual and potential adverse impacts (OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises, chapter II – general policies, para. 10). Due diligence can be included within broader enterprise risk management systems, provided that it goes beyond simply identifying and managing material risks to the enterprise itself, to include the risks of harm related to matters covered by the guidelines (OECD due diligence guidance for responsible business conduct – draft 2.1, p. 8). See page 6 of the OECD easy to use guidance above for a full description of risks.

- Due diligence schemes

Initiatives that can contribute to achieving the aims of the EU regulation and which “aim at breaking the link between conflict and the sourcing of tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold […] Such schemes use independent third-party audits to certify smelters and refiners that have systems in place to ensure the responsible sourcing of minerals. […] The methodology and criteria for such schemes to be recognised as equivalent to the requirements of this regulation should be established in a delegated act to allow for compliance with this regulation by individual economic operators that are members of those schemes and to avoid double auditing” (EU conflict minerals regulation).

- EU regulation

As of 1 January 2021, companies have to comply with regulation (EU) 2017/821 laying down supply chain due diligence obligations for EU importers of tin, tantalum and tungsten, their ores, and gold originating from CAHRAs provided that the annual import volumes exceed those set out in annex 1 to the regulation.

- Ex-post checks

Under the EU regulation, EU country competent authorities will carry out ex-post checks to ensure importers of minerals or metals comply with the regulation. The Commission has provided clear guidance to EU country competent authorities on how such ex-post checks should be carried out. Competent authorities will examine how the companies have complied with the regulation.

- Grievances

Formal and serious concerns and allegations brought forward by any interested party (affected parties or whistle-blowers) who alleges damage or voices a concern or dissatisfaction as a result of the company or its suppliers’ activities and impacts along the supply chain. The grievance involves the expectation that a response or a corrective action will be carried out by the company. Grievance procedures outline the steps that whistle-blowers can take to make a report (and the tools available to do so, such as dedicated hotlines, etc.), and how those reports must be acted upon by designated staff.

- Grievance and whistle-blowing mechanisms

The interrelated processes that support the implementation of a grievance procedure, such as receiving, investigating and responding to a grievance or complaint.

- Mangement system

A regime for achieving the commitments made in a policy. It typically comprises the policy, procedures, resources, roles, responsibilities, reporting obligations and methods, data management, and infrastructure necessary for fulfilling the policy. Greater detail is provided in the FAQs section.

- Mitigation

Mitigation applies when there is a risk of creating or perpetuating harm through your business activities. These activities include contributing to serious abuses, direct and indirect support to non-state armed groups or public or private security forces, or inadequate, inaccurate and fraudulent chains of custody and/or traceability. Through a risk management plan with suppliers and stakeholders, you can source from those areas and suppliers while minimising any negative impact stemming from the risks. Risk mitigation is done once risks are identified or when they materialise and the process aims at reducing their negative impact. When an adverse impact materialises, remediation should also take place.

- The OECD due diligence guidance for responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas

A due diligence framework that was developed to enable companies to identify and manage conflict mineral risks in their supply chains. It consists of the following 5-step framework. (1) Establish strong company management systems. (2) Identify and assess risks in the supply chain. (3) Design and implement a strategy to respond to identified risks. (4) Carry out an independent third-party audit of the refiner’s due diligence practices. (5) Report annually on supply chain due diligence. The OECD DDG has separate supplements for the 3Ts (tin, tantalum and tungsten) and gold. The OECD recommends SMEs to adapt the OECD DDG in accordance with their own size and risk profile.

- Remediation

The OECD DDG for responsible business conduct states that remediation refers both to “the processes of providing remedy for an adverse impact and to the substantive outcomes that can counteract, or make good, the adverse impact, including: apologies, restitution or rehabilitation, financial or non-financial compensation (including establishing compensation funds for victims, or for future outreach and educational programs), punitive sanctions (whether criminal or administrative, such as fines), as well as prevention of harm through, for example, injunctions or guarantees of non-repetition” (OECD due diligence guidance for responsible business conduct, draft 2.1, p. 7).

- Reasonable country of origin inquiry (RCOI)

An investigation conducted to determine whether any tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold (3TGs) in a supply chain originated from a conflicted-affected or high-risk area, or from recycled or scrap sources. The meaning of ‘reasonable inquiry’ depends on several factors including the size of the company, its products, the visibility of its supply chain, and supplier relationships. The Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) provides its members with a list of country of origin information on the source of conflict minerals in 3TG supply chains, to help companies to conform to the OECD DDG. See the RCOI list (full list available to members only).

- Risks and risk assessment

Risks refer to the potentially adverse impacts a company’s operation could have through its business practices, its relationships with suppliers and its relationships with other entities in the supply chain. Through its due diligence process, a company identifies the potential risks of being linked directly or indirectly (for example through your supply chain) to irresponsible mining and processing of minerals in CAHRAs. A company carries out a risk assessment by looking into the factual circumstances of its business activity and assessing the level of risk by evaluating these circumstances in relation to compliance with national and international laws and standards.

- Software as a service (SaaS)

SaaS is a model of software licensing and delivery where the software is granted on a subscription basis and centrally hosted. It is usually accessed by users through a web browser.

- Small and medium-scale enterprises

In the EU, “the category of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is made up of enterprises which employ fewer than 250 persons and which have an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million, and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding €43 million”.

- Supply chain mapping software

Supply chain mapping software helps companies to understand, communicate and gather data from their supply chain, usually through an online platform. These tools enable companies to centrally collate supply chain information, and then analyse and process the information in an efficient manner. This software can also help companies ensure the data they have collected from suppliers are aligned with any necessary legislation or guidelines with which they are required or aiming to comply/conform.

- Third-party audit

A third-party audit in the context of the OECD DDG is a process by which an independent third party verifies compliance with the 5 steps of the due diligence process. The auditor examines the activities, processes and systems used by a company to conduct supply chain due diligence. According to the EU regulation on conflict minerals (article 6), the auditor shall assess the conformity with the regulation of importers’ management systems, risk management and disclosure of information. The auditor shall make recommendations to the auditee on how to improve their due diligence practices. Importers can be exempt from carrying out third-party audits if they can provide evidence which demonstrates that their smelters and refiners comply with the EU regulation. This evidence shall include third-party audit reports.

- Traceability

As per the OECD DDG, traceability is the ability to identify provenance and who has handled the mineral or metal to find out where and from which circumstances it originates. Traceability depends on some process for tracking the minerals as they move along the supply chain (from the point of origin to the smelter or refiner). The paper trail that records the sequence of individuals and companies that take custody of the minerals in the process of moving along the supply chain is called the chain of custody. Note that new technologies are being developed to track and trace minerals.

- Upstream companies

This includes “miners (artisanal and small-scale or large-scale producers), local traders and exporters from the country of mineral origin, international concentrate traders, mineral re-processors, refiners and smelters”.

- Whistle-blower

Any collaborator, contractor, customer and/or third party that raises complaints and/or grievances related to the activities and impacts of the company or its contractors.

FAQ about OECD due diligence guidance

This section will help you find an answer to some of the most pressing questions SMEs ask themselves about due diligence.

SMEs’ frequently asked questions on due diligence

In simple terms, due diligence is how a business understands, manages and communicates about risk. This includes the risks it generates for others, and the risks it encounters through its strategic and operational decisions and actions.

A technical description of due diligence would be as follows: it is the processes through which enterprises identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their actual and potential adverse impacts (OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises, chapter II – general policies, para. 10). Supply chain due diligence is an ongoing, proactive and reactive process through which companies monitor and administer their purchases and sales with a view to ensuring that they do not contribute to conflict or related adverse impacts.

Due diligence can be included within broader enterprise risk management systems, provided that it goes beyond simply identifying and managing material risks to the enterprise itself, to include the risks of harm related to matters covered by the OECD guidelines (OECD due diligence guidance for responsible business conduct, draft 2.1, p. 8). The OECD easy to use guidance (p. 6) provides a full description of these risks.

A company’s aspiration to declare itself ‘conflict-free’ is neither a recommendation of the OECD DDG nor a requirement of the EU regulation.

Doing effective due diligence on your supply chains will help you to source responsibly from conflict-affected and high-risk areas (CAHRAs), not exclude these from your supply chains. This inclusivity of CAHRAs was the original intention of the OECD DDG and the EU regulation.

Regardless of whether you use supply chain due diligence to enable ‘conflict-free’ claims about your business or your products, if you follow the due diligence steps described in the OECD DDG and you manage to demonstrate a significant improvement of your risk management system, then you can claim to be sourcing minerals responsibly.

Just because your company does not have any legal obligations, that does not mean that due diligence is not relevant or useful to you. Moreover, it is possible that your company will come to have obligations in the future. Furthermore, given the global trend towards mainstreaming due diligence across mineral supply chains, you are likely to find your clients increasingly requesting that you do due diligence. Preparedness can save costs and inconvenience at a future stage. It will also help you control risks and nurture value in your business.

Performing due diligence will take some time and resources, but the time you will need will depend on your size and position in the supply chain, the complexity and risk profile of your supply chains, your experience in setting up management systems, and your access to fast-track proportionate solutions. In fact, there is a lot of variability in how a company may conduct due diligence and the OECD DDG is designed for this flexibility. As an SME you are likely to have fewer suppliers than larger companies and to have long-lasting business relationships with them. This should enable you to progressively accumulate the kind of information necessary to set up and do adequate due diligence in a reasonable time frame.

If you are a company with many suppliers, consider joining an industry association to combine forces with other companies and leverage greater power. Also consider introducing management systems (potentially including a data management system that assists the collection, aggregation and reporting of due diligence data). You can find a full list of IT solutions in the due diligence toolbox. A data management system could save you time in collecting and aggregating information and you will be able to focus your time on mitigating risks you identify through the system.

Another way to save time and money is to look into integrated software-based data management and compliance solutions. These can help you increase efficiency and thus minimise costs by combining compliance with different laws and supplier outreach. For instance, some IT solutions can help you comply with requirements/guidance on responsible sourcing as well as comply with several regulatory/legislative requirements in a combined and cost-effective fashion.

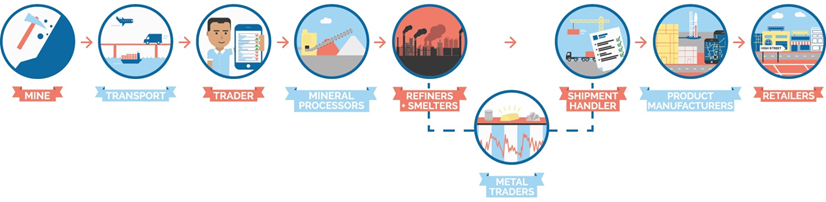

The terms ‘downstream’ and ‘upstream’ are used to indicate different stages of production processes and use in the mineral supply chain and in industry. In simple terms, upstream companies are those active in the stages from extraction up to (and including) smelting and refining. Downstream companies are those that process the output from smelters and refiners into semi-finished products and final products. Look at the supply chain below: all companies to the left of and including the smelters and refiners are companies located upstream, all companies to the right of the smelters and refiners are companies located downstream. The more downstream a company is, the closer it is to the end-users/consumers.

Overview of a mineral supply chain

Companies downstream of the refiners and smelters include metal traders and exchanges, bullion banks, other entities that do their own gold vaulting, component manufacturers, product manufacturers, original equipment manufacturers, jewellery manufacturers and retailers. It also includes other companies using processed metals in the fabrication of products, such as manufacturers and retailers of electronics equipment and/or medical devices. Companies upstream include those active in extraction (artisanal and small-scale up to large-scale producers), local traders and exporters from the country of mineral origin, international concentrate traders, mineral re-processors, refiners, and smelters.

The supply chain illustrated above is simplified and high-level, to show you the typical nodes or stages of the supply chain. However, at each stage or node, you might find many actors. For example, at the ‘mine’ stage, there could be numerous miners, both small and large scale. You might also have different transporters, traders and mineral processors in the supply chain. The ‘refiners and smelters’ stage/node is commonly referred to as a ‘pinch point’, and they supply the metal to numerous downstream companies. There are fewer refiners and smelters compared to the number of companies located upstream and downstream (see also question number 8), hence the idea that they constitute the pinch point of mineral supply chains.

A policy is a document that publicly states certain principles and commitments your company has made on a particular issue. In this case, the policy would state your company’s position in relation to responsible sourcing and your expectations of how suppliers will support you in achieving the policy’s stated objectives. Annex II of the OECD DDG provides a template for a supply chain policy for a responsible global supply chain of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas (CAHRAs).

This annex can be used by and adapted for all companies in mineral supply chains. Your policy should be communicated to your employees and suppliers, for example by publishing it on your website and at your offices and sites, including it in contracts, or sending it to prospective and current suppliers and clients via post or email.

The Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) publishes a link to the supply chain policy of each conformant smelter and refiner in its assessment program. The RMI also provides a grievance mechanism that you can use as example.

If you are a downstream company, check examples of policies from other major companies that are already active in responsible sourcing of minerals. If you are a mid-upstream company, you can find examples of policies on the RMI conformant smelters and refiners page.

How you implement a policy is determined by the procedure set out in it. The procedure should describe the management system you have put in place to ensure you live up to the commitments you have made in your policy. This procedure should specify who is responsible for overseeing its implementation and when and under what circumstances it will be revised. If you need further guidance on how to set up your own management system, you can use the '3Ps checklist: establish strong company management systems (OECD Step 1) through people, policies and procedure (annex 1)'.

If you are a downstream company, doing your due diligence means:

You need to identify the smelters and refiners in your supply chain.

The Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) has developed a Conflict Minerals Reporting Template (CMRT) which is a free, standardised reporting template that you can use to facilitate the transfer of information through your supply chain regarding the mineral country of origin and the smelters and refiners being utilised. You can also use this template to identify new smelters and refiners that need to undergo an audit. Some companies decide to use the template in the original Excel format, sharing it with their suppliers and then collating the information. Other companies may prefer using IT solutions to automate the process (see the due diligence toolbox for a list of IT providers).

Once you have identified the smelters and refiners, check whether the company/ies have successfully passed their audit. Under the EU regulation, the Commission will issue a list of global responsible smelters, taking into account those covered by supply chain due diligence schemes recognised by the Commission. You can also find a list of conformant (that are conformant with the great (RMAP) assessment protocols.) and active (participants in the RMAP and have committed to undergo a RMAP assessment) smelters and refiners on the RMI’s website.

Assess smelters’ and refiners’ due diligence systems against the OECD DDG.

You will need to request information from your suppliers to understand if and how they manage risks. If you are not satisfied with the information provided, you could also request that they provide examples of how they have managed the relevant risks in the past or how they intend to do so going forward.

If you are a small company, you might find it hard to identify smelters and refiners.

In this case, try to cooperate with other companies to identify smelters and refiners in your supply chain. In particular, your suppliers (who in theory should be upstream from you) should be closer to the smelters/refiners in your supply chain, and so may have more information. You can also join industry associations that support their members with their due diligence efforts.

Introduce a supply chain transparency system to map your supply chain.

This will be used to identify smelters and refiners in the supply chain and to identify information about red-flag locations of mineral origin and transit. This information will help you identify countries of origin, transport and transit of metals in the supply chain for each smelter and refiner. The 'due diligence ready!' platform provides a due diligence toolbox which lists information on potential tools that can help you with this.

Keep a record of your due diligence process, communication, decisions made and the reasons for certain decisions being made.

Maintain these records for a minimum of 5 years.

Closely monitor risks when they are identified.

Regularly assess risk – for example annually, depending on the degree of flux in your sourcing practices – to see if anything has changed since your previous risk assessment was carried out.

If you are a company operating upstream, doing your due diligence means:

Clarify the chain of custody.

The chain of custody is the paper trail that records the sequence of individuals and companies that take custody of the minerals as they move along the supply chain.

Understand the circumstances of mineral extraction, trade, handling and export.

A raw mineral is brought to the consumer through multiple actors, which usually includes actors at the following points: “extraction, transport, handling, trading, processing, smelting, refining and alloying, manufacturing and sale of end product” (OECD DDG). Due to circumstances related to the extraction, trade or handling of the minerals, these stages tend to carry higher risks of contributing to conflicts or having negative impacts on human rights. For guidance on how to improve your understanding of these circumstances, refer to the OECD DDG appendix 'guiding note for upstream company risk assessments' (p. 54).

Identify and assess risk.

The 'appendix: guiding note for upstream company risk assessments' contains guidance on establishing on-the-ground assessment teams and recommended questions to guide your risk identification and assessment.

You might not be able to map your entire supply chain within the first year of conducting due diligence but you are expected to work towards this goal (which might be achieved progressively over 2 or 3 years). Remember that the spirit of the OECD DDG is continuous improvement. Perfection is an impossible and unfixed destination when it comes to due diligence!

A risk-based approach could focus on your riskiest suppliers and your ‘critical’ suppliers.

- The riskiest suppliers are those you know are already or are more likely to be sourcing from CAHRAs and/or they could be indicated by the red flags you identify.

- Your critical supplier is not necessarily your biggest supplier in terms of volume or value, but the one that is most interconnected with other distant or immediate suppliers in your supply chain. The critical supplier has the greatest number, diversity and/or connectedness of suppliers and so has the most potential to influence others and/or the greatest exposure to potential supply chain issues. By working closely with the critical supplier, you can have a knock-on effect upon the other companies in the supply chain. You will also use your resources more efficiently and have a greater chance of achieving your objective.

If you are a downstream company, under the OECD DDG you are expected to identify all smelters and refiners in your supply chain. A large number of downstream companies use the Conflict Minerals Reporting Template (CMRT) to identify refiners and smelters in their supply chain. The CMRT form is a standardised reporting template developed by the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) “that facilitates the transfer of information through the supply chain regarding mineral country of origin and smelters and refiners being utilised. The template also facilitates the identification of new smelters and refiners to potentially undergo an audit via the RMI’s Responsible Minerals Assurance Process (RMAP)”. The RMAP “uses an independent third-party audit of smelter/refiner management systems and sourcing practices to validate conformance with RMAP protocols and current global standards. The audit employs a risk-based approach to validate smelters' company level management processes for responsible mineral procurement. Companies can then use this information to inform their sourcing choices”.

Refiners and smelters are expected to provide information on the process or methodology used for their chain of custody. They are also expected to provide information on the circumstances of mineral extraction, handling, trade and export, and the process of assessing the risks in these circumstances. This means that they must describe and explain how they know which entity handled and/or owned the mineral at each point of the supply chain (chain of custody). In addition they should be able to explain how the mineral was extracted, handled, traded and exported (by whom, where, in what time frame, and so on). Knowing these things is the basis of being able to identify and then assess risks.

Step 2, II.B of the OECD DDG stipulates that: “downstream, companies ... may engage and directly cooperate with other industry members ... to carry out the recommendation contained in this section in order to identify the smelters/refiners in their supply chain and assess their due diligence practices”. You are therefore not necessarily expected to do this on your own. There are a number of industry joint initiatives that provide support (e.g. Tantalum-Niobium International Study Center, the Responsible Minerals Initiative (see question 7), the European partnership for responsible minerals, iTSCi, etc.). In this context, it should be noted that the OECD has carried out a pilot project assessing the degree of alignment of industry programmes with the OECD DDG. Such industry programmes (or due 'diligence schemes' as they are referred to in the EU context) may apply for recognition by the EC, and recognised schemes will be listed on the EC’s website.

While companies can use third parties to carry out due diligence tasks, the ultimate responsibility for the adequacy of due diligence remains with your company. It is important to be responsible for your own due diligence and work on mapping the supply chain, one step at a time.

If you have made enquiries or used a reporting form to collect supply chain information from your suppliers and you have not received any answer back, do follow up by email or telephone, repeatedly if necessary. It should help to communicate the importance of the enquiry and the reason for your request.

If you still do not receive an answer, escalate the situation and call your supplier’s senior management to ask why you have not had an answer, what they can do to get you one and in what time frame.

You want to find out why the supplier is not responding. It is possible that

- the form was not sent to the correct person, which is easy to rectify

- the supplier does not understand the reason for the enquiry or its importance (be sure to communicate that, including in commercial terms)

- the supplier does not know how to gather the information

- the supplier is struggling to get responses from their own suppliers

Once you find out why the supplier is not responding, consider how you can help them get this information. If the supplier cannot provide the information due to a lack of capacity or is struggling to get responses back from their suppliers, you can suggest they escalate the situation in order to effectively communicate to their suppliers the necessity of responding to requests. You may also offer to write a letter to their supplier/s to help them justify their requests.

If it is a question of lack of will on behalf of your supplier, consider reaching out to your main customer and/or relevant industry associations/schemes and joining forces to create a combined approach that could help turn a reluctant supplier into a more collaborative one. In the meantime, start scoping alternative suppliers in case you need to disengage and consider communicating this to your supplier as part of your bargaining to get what you need. If the supplier refuses to provide the information you need, the measure of last resort would be to suspend or cease trading with the supplier.

It is important that you save emails, letters and/or minutes of calls documenting all the above steps. These could be valuable sources of information during audits (step 4 of the OECD DDG) and could also enable you to monitor progress made and identify any need for improvements in supplier management.

The risks are listed in the OECD DDG and summarised below.

Serious abuses associated with the extraction, transport or trade of minerals

- Any forms of torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment

- Any forms of forced or compulsory labour

- The worst forms of child labour

- Other gross human rights violations and abuses, such as widespread sexual violence

- War crimes or other serious violations of international humanitarian law (crimes against humanity or genocide)

Direct or indirect support to non-state armed groups or private/public security forces

- Non-state armed groups or public or private security forces illegally controlling mine sites or otherwise controlling transportation routes, points where minerals are traded and upstream actors in the supply chain

- Non-state armed groups or public or private security forces illegally taxing or extorting money or minerals at points of access to mine sites, along transportation routes or at points where minerals are traded

- Non-state armed groups or public or private security forces illegally taxing or extorting intermediaries, export companies or internal traders

Bribery, fraud, money laundering, terrorism financing

- Bribery and fraudulent misrepresentation of the origin of minerals and money laundering

- Non-payment of taxes, fees and royalties to the government

- Financing of terrorist groups

To help companies understand risks in their supply chains and prioritise those risks to enable a more efficient and effective due diligence process the OECD has developed the OECD portal for supply chain risk information.

Start by trying to map your supply chain following the guidance in the previous questions. Then try to identify the presence of any of the following red flags as described in the OECD DDG (which will also be addressed in the forthcoming handbook from the Commission).

Red-flag locations

- The mineral is claimed to originate from a country that has limited known reserves or stocks, likely resources, or expected production levels of the mineral (i.e. the declared volumes of mineral from that country are out of keeping with its known reserves or expected production levels).

- The mineral is claimed to originate from a country through which the mineral from CAHRAs is known or reasonably suspected to transit.

- The mineral is claimed to originate from recyclable/scrap or mixed sources and has been refined in a country where the mineral from CAHRAs is known or reasonably suspected to transit.

Supplier red flags

- Suppliers or other known upstream companies operate in one of the above-mentioned red-flag locations of mineral origin and transit or have shareholder or other interests in suppliers of minerals from one of the above-mentioned red-flag locations of mineral origin and transit.

- Suppliers or other known upstream companies are known to have sourced minerals from a red-flag location of mineral origin and transit in the last 12 months.

Red-flag circumstances

- Anomalies or unusual circumstances are identified through the information collected in step 1 of the OECD DDG, which gives rise to a reasonable suspicion that the mineral may contribute to conflict or serious abuses associated with the extraction, transport or trade of minerals.

Did you identify a red flag?

- No: you do not need to do any additional due diligence. However, ensure a regular review of the risks and keep your management system established and up to date. Remember to do your public reporting (step 5).

- Yes: you should do the following

- Do additional research on the red flags: e.g. read reports

- Consult civil society, local governments, local suppliers and UN agencies, and ask questions to better understand the risks

- If you are an upstream company, establish an on-the-ground assessment team. If you are a small company, you might want to identify initiatives that contribute to carrying out on-the-ground assessments and join forces with other members of the industry. You might also decide to join forces with your suppliers to engage stakeholders on the ground or experts who can provide first-hand information.

The following provide only an indication of possible questions that can be addressed to suppliers to assess the risks identified by the OECD DDG. Note that these questions might need to be adapted based on the company’s role in the supply chain and the profile of the supplier.

You can ask the following questions to your direct supplier

- Who are the key individuals in the organisation (shareholder, senior managers, beneficiary owners, ultimate beneficiary owners)? [Ask for an organigram of the organisation and do a background check on these people. Are they on any sanction lists? Is there any criminal record that concerns you? Is there any Politically Exposed Person listed in the organisation?]

- Where is the company registered?

- Where is the company operating? What kind of activities does the company have in each country?

- Does the company have a licence? [Request a copy. Check the signatures – are they from people in the organigram?]

- Are the areas of operation in or near to conflict and/or presence of armed groups?

- Who are their suppliers and where are they located? (Note: this question is important as your supplier can be located in a low risk area but it could source from suppliers located in medium or high risk areas. You should carry out a risk assessment on the supplier’s country and also on the countries in which its own suppliers – and ideally all the suppliers in the supply chain - are located)

Understanding the supplier’s policies and risk management approach

- Does the company have policies and procedures which cover human rights? [Request a copy when available] (Note: the policies and procedures should address the risks listed under question 11.)

- Does the company have policies and procedures which cover responsible sourcing of minerals? [Request a copy when available]

- Does the company maintain a chain of custody on the minerals it sources? [Ask for the process and procedure followed for this]

- Does the company have policies and procedures which cover anti-money laundering (AML) designed to combat money laundering and financing of terrorism in line with AML-related local and international laws and policies?

- Does the company maintain a register of tax payments? [Ask for evidence]

- Does the company have a grievance and whistleblowing policy and procedure? [Request a copy when available]

- Does the company have risk mitigation procedures for risks identified in your supply chain? [Request risk management plan]

- Does the company maintain an incident report to monitor incident occurrence? [Request a copy]

- Does the company operate in an area where there is risk of children working on mine sites? If yes, how do they make sure children do not engage in hazardous work on and around their concession?

Once you have identified potential risks in your supply chain, you can assess these risks and identify those that are most salient. To identify the most salient risks, you will need to consider the following criteria

Scale: refers to the gravity of the risk. What is the potential impact on people? (As opposed to the usual question: what is the potential impact on the company?) The higher the impact, the higher the scale will be.

Scope: refers to the reach of the risk. How many people could be affected by this risk? The higher the number, the higher the scope will be.

Irremediable character: refers to the limits on the ability to restore the individuals or environment affected to a situation equivalent to their situation before the adverse impact. Would the impact become irremediable if you did not intervene? You need to do something before the negative impact of a risk materialising becomes irremediable. When a risk that materialises would be hard to remediate, then the relevant risk should be considered as a priority.

The OECD guidance for responsible business conduct includes some examples on how to apply the criteria of scale, scope and irremediable character.

The table below takes an example from the OECD RBC guidelines of an adverse impact.

| Adverse Impact | Examples of scale | Examples of scope | Examples of Irremediable Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption |

|

|

|

| Human Rights |

|

|

|

The OECD DDG is aligned with the United Nations guiding principles on business and human rights, which asks companies to focus on salient human rights and risks of conflict financing issues. For further guidance on human rights salient risks, see this page and video.

The OECD DDG includes a definition of what constitutes a CAHRA. To facilitate compliance with the EU regulation, the Commission prepared non-binding guidelines in the form of a handbook for economic operators, explaining how best to apply the criteria for the identification of CAHRAs, and has called upon external expertise to provide an indicative, non-exhaustive, regularly updated list of such areas.

You should use this tool in carrying out due diligence on an existing, a prospective or a new supplier or customer. The above-mentioned CAHRAs list will be updated on a regular basis, as the situation and circumstances in a given geographic area can frequently change and a country or area that is not conflict affected or high risk at the moment might become so later on. Remember that this is an indicative, non-exhaustive list and you should do your own research to further identify all CAHRAs.

It is first important to recall that the aim of the OECD DDG is not to prevent sourcing of 3TG from CAHRAs, but rather to ensure that such sourcing does not lead to outcomes such as financing of armed groups, serious economic crimes and human rights abuses. In order to prevent or mitigate an identified risk, companies can either continue to trade and take risk mitigation efforts, suspend trade while pursuing such efforts, or disengage with a supplier after failed attempts at risk mitigation.

Here are some benefits to sourcing from CAHRAs

- Excluding a supplier of CAHRA provenance as a primary mitigation strategy is not recommended by the EU regulation or the OECD DDG. The purpose of these 2 compliance frameworks is to help avoid political or commercial sanctions on the export of minerals from CAHRAs.

- The minerals business is a vital lifeline to many individuals, families and communities during times of conflict or political and economic upheaval. If these people lose the market for their minerals, they may lose income or may be forced to lower prices or sell to other buyers with less favourable terms. This can make them even more vulnerable to human rights abuses and reduce their ability to cope with risk events.

- Remaining engaged with CAHRAs, in combination with adequate and appropriate due diligence measures, is an opportunity for you to deliver a positive economic impact in a fragile society. This can provide you and your customers with opportunities for positive storytelling as part of proactive or reactive communications strategies. Remaining loyal to suppliers facing a deteriorating political situation can generate reciprocal loyalty and other benefits in the longer term.

- Under certain conditions, remaining engaged with producers in CAHRAs is in line with the OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises.

If your company discovers that one or more of your suppliers sources minerals from a CAHRA, you should not stop doing business with them as the first response. If you intend to continue to source from the CAHRA, you must make all reasonable efforts to manage risks and provide evidence (e.g. audits, due diligence documents) to your clients that your due diligence (and thus that of your supplier) is reliable and that there are virtually no risks of financing conflicts or violating human rights. Doing so should increase their acceptance of minerals from CAHRAs in their supply chains. If they ask you to stop sourcing from CAHRAs, open a conversation to see how rigid this view is. Changing suppliers or provenances can be challenging and costly, so you have to be sure that it is necessary for their, and your, business.

Remember! Due diligence is a process! You won’t be able to fix everything at once and you won’t be perfect from the start. You need to demonstrate that you are progressively improving how you do due diligence and you can improve it over time. If you follow the due diligence steps and you manage to demonstrate a significant improvement in your risk management system, then you can claim to be sourcing minerals responsibly.

You can do the following things to help.

Support your supplier by offering to draft a letter that the supplier can use to better explain and strengthen the reasons why it is requesting that information from its suppliers. If one of its suppliers is being especially difficult, you could offer to join a call with both entities to help your supplier communicate the importance and benefit of providing the requested information.

Suggest that your supplier starts including disclosure requirements in new supplier contracts.

Discuss with your supplier whether joint solutions can be identified. Together you can approach industry associations and ask them whether they can provide support.

Contract specialists in the field of sustainability and responsible sourcing to carry out the most critical tasks, such as performing a situational analysis of the supply chain or carrying out an on-the-ground assessment of very high-risk suppliers in the upstream segment. This may be an expensive undertaking, depending on the location of your suppliers. It may be possible to ask your suppliers to share the cost of this service so that it is manageable.

Share your policies and procedures for due diligence with your suppliers. Not only will this help them get their systems in place faster, but it will mean that their systems will be more likely to be aligned with your own, which will increase your trust in what your supplier then does for due diligence. A further benefit is that the supplier may give you feedback or ideas for streamlining or improving your own policies, e.g. how to achieve the standards you pursue while increasing feasibility for suppliers. This is invaluable in the spirit of continuous improvement and pursuit of efficiencies and optimal performance.

Introduce your supplier to industry schemes, joint initiatives or specialist service providers (e.g. IT companies) that could help them get the necessary systems in place in a cost-effective manner.

Share this guidance with your supplier, to help them understand how to better engage with their own suppliers.

First, ask your suppliers to share their own due diligence and mitigation procedures on responsible mining and/or sourcing. Request the following information

- Their supply chain policy for responsible sourcing of minerals. The OECD provides a template for such a policy in annex II of the OECD DDG.

- The management system (e.g. procedure, flow chart) they have in place to assess risks and agree on mitigation strategies.

- The data collection and data management system they use to manage supply chain information.

In this way you can assess if they have due diligence systems in place that are adequate and aligned with your own, meaning whether they are good enough for you to be confident that they can manage risks should they arise.

You should then establish with your supplier how they will communicate incidents that arise to you, how these are being or have been handled, and within what time frame following the supplier becoming aware of the incident.

If your supplier is frustrated by your requests, try the following

If they are aggressive, do not respond angrily and try to avoid any emotional escalation. Try to listen to their concerns and explain that you faced similar challenges and you will be happy to share how you handled them. Make sure your supplier understands that due diligence is a process which might not be perfect from the start, but that it is important to demonstrate progressive improvement in how a company does due diligence and that this can help them lock value into their business.

Clarify that many countries are adopting a regulatory framework on responsible supply chains. Explain that you are probably among the first clients to have asked questions on their due diligence but that many others will soon do the same given the rising mandatory legislations on responsible sourcing.

Offer support and make sure you have the same understanding of due diligence. Explain that you are happy to discuss with them how they can set up their risk management system and all their policies and demonstrate that they have these in place. Provide examples of policies, how to identify red flags and how to mitigate risks and share with them information that is available online.

Prepare your suppliers by informing them in advance about your future requests. Do not wait until the last minute to ask your suppliers for information about their due diligence system. Since due diligence is a process, you will have to give your suppliers early warning and enough time to set their systems in place.

Encourage your suppliers to join existing industry initiatives. Explain that these initiatives offer opportunities to learn from peers about their due diligence, to have access to information and risk assessment tools, and also to network with new potential clients.

Share the ”due diligence ready!” portal with them. ”The due diligence ready!” portal is a primer to the OECD DDG. If they better understand the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of due diligence, they may be more welcoming of your enquiries.

If a supplier needs to set up a reliable risk assessment and mitigation strategy, ask them to establish one within a set time frame. You may decide to suspend your relationship with them until this issue has been addressed, or indicate that you will have to suspend within a given time frame, depending on the amount of risk you feel you would be taking on to continue trade without these procedures in place. You may also choose to provide them with advice on setting up these systems or direct them to information that could help them.

‘Mitigation’ of a risk or potential adverse impact refers to actions taken to reduce the likelihood of certain adverse impacts occurring. You can, for instance, ask your suppliers to share their policies with you and explain how they identify and manage risks. If your suppliers do not have this system in place, you can ask them to create one within a set timeline and then provide updates to you. You can also offer basic training to your suppliers. This can be in the form of sharing your policies and procedures as examples or providing some additional guidance and explanation over the phone. Also, make a list of all the online resources that you found helpful and share these with your suppliers.

Mitigation with respect to actual adverse impacts refers to actions taken to reduce the extent of an impact. If an incident is occurring or has occurred, ask your suppliers what they are doing to avoid the same incident reoccurring or having a greater impact. Please also refer to annex III of the OECD DDG: 'Suggested measures for risk mitigation and indicators for measuring improvement'.

The OECD guidance for multinational enterprises (OECD MNEs) indicates the following options in relation to mitigation measures in a business relationship:

- continuation of the relationship with a supplier throughout the course of risk mitigation efforts

- temporary suspension of the relationship while pursuing ongoing risk mitigation

- or, as a last resort, disengagement with the supplier either after failed attempts at mitigation, or where the enterprise deems mitigation not feasible, or because of the severity of the adverse impact

Make sure you keep a record of all email exchanges, the minutes of your calls, any exchanges with suppliers or stakeholders, and any decisions made, as these will provide hard evidence of your due diligence efforts.

Any actual impact then requires remediation (see question 22).

Remediation according to the 'United Nations guiding principles on business and human rights' is the process or act that provides remedy, meaning that process through which a company restores people or groups negatively affected by the materialisation of a risk to the situation in which they would have been if the incident had not occurred.

When a risk materialises and is reported to you by one of your suppliers or other parties, you should ask your suppliers what remediation measures they have put in place. The supplier or other party will be expected to determine appropriate forms of remedy by

- looking at existing standards which might already be existing internationally and locally to determine appropriate forms of remedy

- looking for precedents and what was done in similar cases

- taking into account stakeholders’ preference, in the sense that those affected should be consulted on what is best for them

This is particularly challenging when instances of the worst forms of child labour or forced labour are linked to your suppliers. In these instances, you could demand that victims are referred to local relevant authorities or local initiatives that protect vulnerable children.

Also, liaise with relevant industry associations and ask for guidance and support, including how they can help you facilitate risk mitigation and prevent these from materialising.

See some notes on the specific risks below.

Worst forms of child labour: children should be protected from the worst forms of child labour. Nevertheless, remediation should also assess the impacts of immediate dismissal of child labourers by taking into account issues such as replacing the lost income for their families or risks of children being forced in other illicit activities such as use of children in armed conflict, child prostitution, etc.

Forced labour: compensation and access to justice are common remediation actions with respect to forced labour. The company might want to get involved to help victims since obstacles to access remedies are often encountered.

Do not panic! But treat this seriously by taking, for instance, the following steps

- report the findings to your senior manager

- disengage from suppliers that are committing serious human rights abuses or providing direct or indirect support to non-state armed groups

- continue sourcing but mitigate for all other annex II risks (such as money laundering, etc.) with a measurable time frame for specified improvements

- Do risk mitigation by

- making a plan on how to eliminate the risks you have identified

- monitoring the risks in the supply chain with the support of stakeholders

The OECD DDG states: “As detailed in step 3(D) of annex I, companies should conduct an additional risk assessment on those risks requiring mitigation after the adoption of the risk management plan. If within 6 months from the adoption of the risk management plan there is no significant measurable improvement to prevent or mitigate the risk of direct or indirect support to public or private security forces, companies should suspend or discontinue engagement with the supplier for a minimum of 3 months. Suspension may be accompanied by a revised risk management plan, stating the performance objectives for progressive improvement that should be met before resuming the trade relationship.”

Please also refer to annex III of the OECD DDG (see question 21): 'Suggested measures for risk mitigation and indicators for measuring improvement'.

As defined in ISO 19011:2011 (guidelines for auditing management systems), an audit is a “systematic, independent and documented process for obtaining audit evidence records, statements of fact or other information which are relevant and verifiable and evaluating it objectively to determine the extent to which the audit criteria set of policies, procedures or requirements are fulfilled”.

3T smelters/refiners and gold refiners that want to comply with the OECD DDG (or with the EU regulation, which includes an audit requirement - with limited exceptions - to all importers of 3TG irrespectively whether the company is a smelter/refiner) are subject to third-party audits.

The purpose of third-party audits is to provide evidence that the measures put in place are sufficient to comply with the OECD DDG (or with the EU regulation, which is consistent with it). Audits can also be helpful in verifying that any problems within the management system detected in the past have been addressed, and in identifying any improvements that can be made to the system.

First, make sure you know and understand the requirements of the standard you want to comply with, specifically that your supply chain due diligence policies, processes and procedures are aligned with the model supply chain policy in annex II to the OECD DDG (3rd edition 2016).

If you don’t know or are having issues understanding these, seek advice sooner rather than later!

To get ready for the audit, you can use the ‘general preparation for an audit – a good practice guide’.

You should also visit the European Commission website’s list of all due diligence schemes recognised by the Commission (upcoming). Such schemes typically offer independent third-party audits to ascertain that a company has systems in place to ensure the responsible sourcing of minerals (see also question 28).

On audits

What is the audit process?

Once the auditor has been chosen, they will provide your company with an audit plan and checklist.

The audit plan and the audit checklist will provide you with the information and evidence that the auditor must check to ensure your company is in compliance with the EU regulation.

Logistical arrangements will then be organised and agreed upon between your company and the auditors. Give your company as much time as possible to prepare for the audit.

Who will conduct the audit?

You should use an auditor that is independent from your company and has knowledge of supply chain due diligence policies, procedures and techniques as well as the social, cultural and historic context of CAHRAs.

What happens if any issues are discovered during the audit process?

If you belong to an industry programme promoting due diligence, that programme will normally expect you, and be able to help you, to address the issues encountered. If you have legal obligations under e.g. the EU regulation, you may be subject to an ex-post check by the competent authority in your EU country, which will look at the results in detail as part of broader activities to determine whether you comply with the obligations.

Why are improvement plans necessary?

One of the fundamental objectives for the audit is to provide interested parties with evidence that companies are following a process of continual improvement to their supply chain management

If you need to undergo an audit and don’t know where to find an auditor, get in touch with an industry programme set up to foster responsible due diligence. The OECD alignment assessment of industry programmes includes a number of such programmes, focusing on specific metals or minerals.

Such industry programmes (or 'due diligence schemes' as they are referred to in the EU context) may apply for recognition by the EC, and recognised schemes will be listed on the EC’s website.

Reporting templates and IT systems are available to help you gather all relevant information from your suppliers and/or to communicate with your customers. You can find more in the 'due diligence toolbox'.

If your customers request that you complete reports that are different from each other, encourage them to use reporting tools that are in line with data exchange standards.

If your customer does not take your advice, you will have to complete the reporting template of their choosing, or risk jeopardising your relationship with them. However, do communicate your concerns to relevant industry and EU initiatives, as your suggestions will help to ensure these associations can come together to identify solutions to problems such as these to benefit the industry as a whole.

If you do not speak the relevant language, write your report in your own language and commission a professional translation or use online free translation tools. If your suppliers do not speak your language, translate key policies and communications into their language, as it is important that these are clearly understood by your suppliers. You can also approach industry associations and EU countries’ competent authorities to seek further support.

Other FAQ

This section will help you find an answer to some of the most pressing questions SMEs ask themselves about due diligence.

No (as of 12/2022).

With regard to the simplification according to Art. 6(2) of the Regulation, a simplification is currently already possible. The exemption according to Art. 6(2) of the Regulation does not depend on recognised systems according to Art. 8 of the Regulation or the list of global responsible smelters and refiners according to Art. 9 of the Regulation. However, as the latter are not yet available, substantive evidence, including third-party audit reports on audits, demonstrating that all smelters and refiners in the supply chain comply with the provisions of the Regulation must be provided.

With regard to simplification according to Art. 7(1) of the Regulation, simplification is currently not possible, as there is no system recognised by the EU Commission according to Art. 8. This is not possible without recognition by the EU Commission.

In general, it applies to both simplifications that the use of a recognised system alone does not constitute evidence of compliance with the due diligence obligations but is only to be understood as evidence in connection with the audit obligation. Companies bear the responsibility for compliance with due diligence obligations, and this cannot be delegated to systems. Systems only serve as support.

Yes, the due diligence requirements are mandatory, and the necessary evidence must be provided, even if no supply chain due diligence system has been recognised as equivalent to Regulation (EU) 2017/821 to date. The Regulation can be complied with without systems or without a list of responsible smelters and refiners. Even if systems were recognised, Art. 6(2) of the Regulation would only exempt Union importers from their own audit obligation under Art. 6(1) of the Regulation. The other due diligence obligations will continue to exist, and corresponding evidence must be provided.

No, if supply chain due diligence systems are recognised as equivalent to Regulation (EU) 2017/821, this recognition only applies from the date of recognition. Systems can therefore only contribute to achieving the objectives of the Regulation in the future and are not considered as evidence of past due diligence measures.

The Commission has received and will start analysing the EU countries’ annual implementation reports by 30 June 2023. These will be the first reports reflecting on the ex-post compliance checks undertaken by the member state competent authorities (MSCAs), covering the year 2022. Therefore, no data is available as of yet.

The effective and uniform implementation of the Regulation is the responsibility of EU MSCAs (member states competent authorities) (Article 10 (3) of the Regulation). The Commission supports the implementation of this Article by providing opportunities for exchange and coordination among MSCAs via the Expert Group on Responsible Sourcing of 3TG. Details of the enforcement practices of MSCAs are known primarily by the EU country and may, at the discretion of the EU country, be shared with the Commission by summer 2023 via the annual implementation reports that will be reviewed and analysed.

As the findings of the first year of ex-post checks (reference year 2022) will be covered in this year’s annual implementation reports by MSCAs, this information is not yet available.

The Conflict Minerals Regulation is considered as lex specialis, covering the specific supply chains of 3TG and the specific risks associated with conflict, as per the OECD Guidance. The ongoing review of the Regulation will also look at the question of the interplay of this Regulation with other related pieces of legislation, such as the CSDDD, the Batteries Regulation or the Critical Raw Materials Act.

From a due diligence practice perspective, companies should not ‘assume’ the outcomes of risk assessments. It is every entity’s responsibility to carry out due diligence on its supply chain. As per due-diligence leading practices and guidance, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, companies retain individual responsibility for their due diligence exercises. Whether a specific material could be linked to conflict financing and related risk will also depend on the actual origin of the minerals, since companies in Europe might be processing 3TG, but they most likely sourced the raw material from elsewhere.

From a due diligence practice perspective, although metals might be processed/manufactured in the EU, the raw materials might have a different origin. It is therefore worth verifying with the EU supplier what kind of processes it has in place to perform due diligence checks on its own raw materials suppliers.

From the perspective of the Conflict Minerals Regulation, the mandatory due diligence requirements only apply to imports into the EUof 3TG, as per the combined nomenclature (CN) codes of the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation (EU) 2017/821 (see definition of Union importer in Article 2 (l) – “any natural or legal person declaring minerals or metals for release for free circulation within the meaning of Article 201 of Regulation (EU) No 952/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council or any natural or legal person on whose behalf such declaration is made)”.

As a general principle, from a due diligence practice perspective, actions and monitoring activities will depend on risks that have been identified (location being one factor, but not the only one). A supplier based in Europe could still be connected to salient risks and/or adverse impacts in relation to its own operations or its supply chain. As a result, should the due diligence process (i.e. identification of risks connected to that supplier) identify salient risks which might require monitoring through third-party audits, then audits should be considered. However, it is important to recognise that audits are not the only tool for monitoring suppliers’ performance, and companies are expected to engage suppliers on the basis of risks and adverse impacts identified, and agree on a strategy to mitigate, address and manage those risks and adverse impacts.

In case the company is seeking compliance or to adhere to a voluntary industry standard, then the requirements of that standard with respect to third-party audits should be considered.

RMI members are notified of each CMRT revision via email. Unfortunately, RMI does not have a channel to make non-members aware of those revisions. As there is a regular revision process, substantial revisions are published only once each year.

Contacts in EU countries

This section provides a list of the official EU country competent authorities, an edited version of that list with additional contact information only valid for this portal and other national authorities responsible for ensuring uniform compliance with the EU regulation.

Official list of EU country competent authorities

List of EU country competent authorities complemented with additional contact information only valid for this portal